« En réalité, nous connaissons les choses de notre monde non pas comme des objets fixes et déterminés, mais plutôt comme des personnes familières ou des étrangers, des proches de confiance ou des voisins gênants, des alliés, des marginaux ou des camarades fantasques et, même, dangereux. [...] Tous ces êtres participent, avec moi, à l’émergence continue du réel. Aucun d’entre eux, selon mon expérience, n’est totalement inerte ou inanimé. »

“We know the things of our world not, in truth, as determinate objects, but as acquaintances and strangers, as trusted familiars and as troublesome neighbors, as allies and misfits and moody, dangerous comrades ... All of these beings are participant, with me, in the ongoing emergence of the real. Not one of them, in my direct experience, is utterly inert or inanimate.”

David Abram - Becoming Animal - An Earthly Cosmology

1-

Une des dernières images de mon livre Les affluents montre quelques roches formant un bassin circulaire inondé par la marée montante du fleuve Saint-Laurent. Au moment de photographier cette petite installation, je me remémorai les nombreuses fois où j’avais moi-même, d’abord en tant qu’enfant puis en tant que père, assemblé ainsi des pierres afin de créer un enclos marin pour y déposer les petits poissons et les écrevisses capturés lors d’après-midis d’été, passés près du ruisseau coulant sur la terre familiale.

Sous un ciel gorgé d’une pluie à venir, je fis quelques images de cet assemblage précaire, sachant que les mouvements de l’eau allaient probablement bientôt le faire disparaître. Plus tard, alors que je travaillais sur mon livre, la symbolique de cette submersion m’apparut signifiante et j’utilisai l’une de ces images pour clore ma série, dont l’objectif était d’évoquer la relation naissante de mes enfants avec la nature et certains lieux importants de notre histoire familiale. La photographie témoignait, me semblait-il, du caractère éphémère de toutes ces expériences qui ont tôt fait de se transformer en vagues impressions lointaines ou en flashs qu’on savoure avec étonnement lors de moments inattendus offerts par la mémoire.

Au-delà des histoires personnelles évoquées par ces pierres submergées, c’était maintenant l’origine de cette intervention furtive qui m’interpellait. Le geste posé sur le paysage symbolisait le dialogue et l’échange, tout comme il représentait les vestiges d’une relation fondée sur l’expérience vécue de ces espaces. Certes, on avait probablement déplacé ces roches naïvement, pour jouer ou simplement pour passer le temps, mais on avait néanmoins parlé au paysage et écrit à sa surface, dans un moment de symbiose auquel je pouvais m’identifier.

One of the last images in my book Les affluents shows some stones forming a circular basin that is being flooded by the rising tide of the St. Lawrence River. As I photographed this human-made arrangement, I recalled the many times that I myself, first as a child and then as a father, had assembled stones in the same way to create a pond in which I would place the small fish caught during summer afternoons spent near the stream running through my family’s land.

Under a sky swollen with rain to come, I made a few images of this precarious structure, knowing that the waves would probably soon wash it away. Later, while working on my book, I found the symbolism of this submersion meaningful, and I used one of these images to conclude the series, in which I wanted to evoke my children’s nascent relationship with nature and certain important places in our family history. The photograph bore witness, I thought, to the ephemerality of all these experiences, which were quickly transformed into vague, distant impressions or flashes to savour with amazement at unexpected moments offered by memory.

Beyond the personal experiences evoked by the submerged stones, the origin of this furtive intervention in the landscape led me to reflect on the nature of the interaction that had occurred at this site. The gesture, it seemed to me, symbolized both dialogue and exchange, just as it represented the vestige of a relationship based on the lived experience of these spaces. Of course, someone had probably moved the rocks innocently, playing or simply passing the time, but they had nevertheless spoken to the landscape and written on its surface in a moment of symbiosis to which I could relate.

2-

Mettre fin à un projet laisse habituellement quelques images en suspens, celles étant trop étrangères aux réflexions du moment et ainsi renvoyées à un espace indéfini de la pensée, peuplé de fragments épars et hétéroclites qui formeront éventuellement quelques constellations d’idées nouvelles. C’est en explorant des boîtes remplies de ces images orphelines (parce que ce bel « espace indéfini de la pensée » s’incarne aussi dans quelques boîtes empilées dans les placards et dans d’autres espaces obscurs de la maison) que je retrouvai par hasard une diapositive grand format datant de 2006. On y voit une sorte d’abri fait de branches et d’herbes d’automne, résultat d’un avant-midi de travail en forêt pendant lequel je m’étais adonné au jeu improvisé de la construction d’un petit refuge. La photographie documentant ce travail n’avait jamais trouvé sa place dans mes projets, mais elle résonnait maintenant en harmonie avec quelques intuitions parcellaires.

À peu près au même moment de l’année, tandis que je marchais au crépuscule dans un petit boisé près de la maison, la lumière en contre-jour changea drastiquement ma perception des lieux, m’éblouissant dans une sorte d’agressivité inattendue. Ne tolérant pas pour sa part un tel aveuglement, l’appareil photo se dressa devant la lumière sans pouvoir en contenir l’assaut : au centre du cadre de mon image apparut un spectre rosâtre, témoignant des limites technologiques de l’appareil et du caractère parfois étonnamment poétique des effets résultant de celles-ci.

Tout comme pour la photographie du cercle de roches de mon projet précédent, la diapositive retrouvée montrait un geste posé dans le paysage. L’image captée à contre-jour, quant à elle, faisait apparaître l’intervention du paysage à l’intérieur même de mon action photographique. L’une montrait un paysage transformé par mon passage, l’autre la trace que ce même paysage avait laissé sur mon image. J’épinglai ces deux images sur mon mur et retournai à mes lectures.

Bringing a project to an end usually leaves a few images in abeyance, as they’re too foreign to the current reflections and are thus bound for an indefinite space of thought, populated by scattered and heterogeneous fragments that will eventually form a few constellations of new ideas. It was while exploring boxes filled with these orphaned images (because this beautiful “indefinite space of thought” is also embodied in a few boxes piled up in closets and other obscure spaces around the house) that I stumbled across a large-format slide dating from 2006. It shows a shelter of sorts made of branches and autumn grasses, the result of a morning’s work in the forest, where I’d been playing the impromptu game of building a little refuge. The photograph documenting this task had never found its way into my projects, but now it resonated in harmony with a few haphazard intuitions.

Around the same time of year, as I was walking through a small wooded area near my home at dusk, the backlight drastically changed my perception of the surroundings, dazzling me with a kind of unexpected aggressiveness. The camera couldn’t tolerate such blindness or withstand the assault of the light: it created a rose-coloured halo in the centre of my image, testifying to the limitations of its technology and the sometimes surprisingly poetic qualities of the resulting effects.

As had the photograph of the rock circle, the recovered slide showed a gesture made within the landscape. The image captured with the backlight showed the landscape’s intervention in my photographic action. So, one showed a landscape transformed by my passage, the other the trace that this same landscape had left on my image. I pinned these two photographs on my wall and returned to my readings.

3 -

Je ne savais plus exactement pourquoi j’avais quitté le sentier. La montée était abrupte. Mon oncle, qui habite les lieux, avait pourtant creusé dans la pente naturelle de la terre un chemin de traverse qui lui permettait, au printemps, de remonter avec le tracteur les barils d’eau d’érable ou, le reste de l’année, les longs billots de bois destinés au moulin. S’il avait pris la peine de tracer un chemin afin de nous éviter la difficile remontée vers le rang 3, pourquoi couper ainsi au travers de la pente, au milieu des branches indomptées et d’une terre meuble à peine tenue par les racines des érables et des merisiers ?

Malgré l’affection pour ces lieux qui nous unissait, nos rapports à la forêt étaient bien différents. J’admirais secrètement chez mon oncle la connaissance détaillée des changements de la nature, mais très rarement avions-nous partagé notre émerveillement face à une ondée spectaculaire ou une débâcle printanière. Tous deux discrets de nature, nos échanges se limitaient à des observations factuelles quant aux événements ayant marqués les lieux depuis ma dernière visite. L’éboulement avait-il englouti une plus grande part de pente du terrain cette année ? La saison des sucres avait-elle été fructueuse ce printemps ? Intérieurement, je me demandais quelle place pouvait occuper la rêverie dans le quotidien de celui qui doit prendre soin ou tirer profit d’une parcelle de territoire.

En tant que visiteur occasionnel, j’abordais ces espaces avec l’imagination et le pragmatisme du randonneur, détaché de la nécessité de les rendre profitables, que ce soit à des fins de culture acéricole (comme c’était le cas ici) ou pour tout autre usage productiviste. Ainsi, j’étais souvent à la recherche de nouveaux chemins afin d’errer autrement dans ces lieux familiers, n’y cherchant rien de particulier sinon une forme de dépaysement susceptible de m’amener vers de nouvelles images. J’avais hérité du côté cérébral de mon père et bien que l’intelligence d’une belle coupe sélective m’impressionnât – en favorisant, par une certaine aération de la forêt, la pousse des arbres les plus prometteurs –, le flâneur introverti n’était jamais très loin, en attente des dérèglements de l’ordinaire et s’excitant lorsque le réel, soudainement, se glissait dans les habits excentriques de l’insolite.

Toujours est-il que je m’agrippais aux petites pousses des peupliers, jaugeant leur capacité à résister à l’étirement que je leur infligerais, et tentant du même coup d’éviter le piège d’un petit tronc en apparence sain à sa base, mais qui me ferait perdre l’équilibre parce que complètement sec à sa cime, mort parmi le vivant.

I no longer knew exactly why I had left the trail. It was a steep ascent. My uncle, who lived on the property, had dug a path across the natural slope of the land so that in spring he could haul up the barrels of maple sap with the tractor, and the rest of the year the long logs bound for the mill. If he’d taken the trouble to lay out a path so that we wouldn't have to make the difficult climb up to the road, why cut across the slope here, amid untamed branches and loose soil barely held together by the roots of the maple and cherry trees?

Despite our shared affection for these places, our relationship with the forest was very different. I secretly admired his detailed knowledge of nature’s transformations, but very rarely had we shared our wonder when faced with a spectacular storm. We were both discreet by nature, and our exchanges were limited to factual observations on the events that had marked the area since my last visit. Had the landslide swallowed up more of the slope this year? Had the maple sugaring season been fruitful this spring? Inwardly, I wondered what part daydreaming could play in the daily life of someone who has to care for or profit from a piece of land.

As an occasional visitor, I approached these spaces with the imagination and pragmatism of a hiker, detached from the need to make them profitable, whether for maple syrup production (as was the case here) or for any other productive use. As a result, I was often on the lookout for new ways to wander these familiar places, seeking nothing in particular other than a change of scenery that might lead me to new images. I had inherited my father’s cerebral side, and although I was impressed by the intelligence of a fine selective cut – which favours the growth of the most promising trees by thinning the forest – I was never very far from the introverted flâneur, waiting for disturbances of the ordinary and getting excited when the real suddenly slipped into the eccentric garments of the unusual.

Still, I grabbed onto little poplar saplings, testing their capacity to bear my pulling on them. At the same time, I was trying to avoid the trap of supporting myself on a small trunk that looked healthy but would cause me to lose my balance because its crown was completely dry – the dead among the living.

4-

Malgré l’automne tardif, les rayons du soleil me réchauffaient le dos tout en éclairant le terrain devant moi d’une lumière presque perpendiculaire à la pente. Quelques champignons ayant survécu à l’assaut des premières gelées, les écorces depuis longtemps tombées, les aiguilles d’une épinette noire et l’émanation fraîche de l’humidité du sol s’harmonisaient à l’effort physique me laissant haletant et m’obligeant à m’arrêter pour souffler un peu. Une fois retourné vers la lumière, j’aperçus par une trouée dans les arbres la pente douce qui remontait de l’autre côté de la rivière, formant ainsi une vallée respectable en dépit du peu d’altitude que ces dénivelés arrivaient à atteindre.

Sur le sol, une longue racine attira mon attention. Enroulée presque parfaitement sur elle-même, elle formait un cercle mystérieux qui évoquait un symbole issu d’un autre lieu et d’un autre temps. Que la nature me parlât, je n’en avais aucun doute : mon corps entier ressentait chaque instant passé en forêt, humait les odeurs, ressentait les textures des éléments que je touchais dans mes déplacements et écoutait la faste trame sonore des bois. Mais qu’un langage fait de symboles et de signes pouvant être lus ou interprétés puisse exister – cela faisait appel à un degré de fantaisie que je n’étais pas complètement prêt à me reconnaître.

Il y avait cependant ce balai de sorcière qui, à contre-jour, m’était apparu plus tôt comme le curieux présage d’un nœud intérieur à défaire afin de faire confiance à ma pratique de l’image, paraissant parfois étrangères aux approches contemporaines du médium. Il y avait aussi cette souche d’arbre, polie par le passage de l’eau à sa surface, coincée dans le lit de la rivière et se transformant en ossements lisses, comme un squelette résilient. J’avais trouvé là une pierre, elle aussi bien bloquée dans un espace qui ne semblait pas lui être destiné, mais créant tout de même un alliage d’une beauté surprenante. J’y voyais la manifestation d’une faculté de créativité, cette impulsion autrement considérée comme appartenant exclusivement à l’humain. À bien y réfléchir, la possibilité d’un changement de perspective semblait maintenant nécessaire afin d’être un peu plus « en phase avec la nature ambiguë et provisoire de l'expérience sensorielle », comme le disait le philosophe David Abram. Celui pour qui « aucun phénomène n'est totalement passif, sans efficacité ni influence » accaparait de plus en plus mes pensées, m’invitant à reconnaître dans la moindre manifestation du réel une influence active, ayant sa propre agentivité et son rôle unique à jouer dans la trame narrative de mon existence. Ainsi, sans trop m’en rendre compte, à mesure que je produisais des images, que je lançais les coups de flash lumineux dans la noirceur environnante ou que je réalisais quelques interventions furtives dans le paysage, je devenais animiste.

Despite the late autumn, the sun’s rays warmed my back and illuminated the terrain ahead with a light that was almost perpendicular to the slope. A few mushrooms that had survived the assault of an early frost, long-fallen tree bark, the needles of a black spruce, and the fresh scent of moist soil harmonized with the physical effort that left me panting and forced to stop for a breather. As I turned back toward the light, I could see through a gap in the trees the gentle slope that rose on the other side of the river, forming a respectable valley despite the low altitude that these hills were able to reach.

On the ground, a long root caught my eye: it curled almost perfectly around itself, forming a mysterious circle and evoking a symbol from another time and place. That nature spoke to me I had no doubt, as my whole body felt every moment spent in the forest – smelling the odours, feeling the textures of the things I touched as I went, and listening to the rich soundtrack of the woods. But that there could be such a thing as a language, made up of symbols and signs that could be read or interpreted, appealed to a degree of fantasy that I wasn’t quite ready to admit to myself.

There was, however, a witch’s broom that, with backlighting, had struck me earlier as a curious omen of an inner knot to be untied in order to trust my image-making practice, which sometimes seems at odds with contemporary approaches to the medium. There was also a tree stump, polished by the passage of water over its surface, wedged in the riverbed and being transformed into what looked like smooth bones, a resilient skeleton. A stone, also lodged where it seemingly shouldn’t be, created a surprisingly beautiful assemblage. I saw it as a manifestation of creativity, that impulse otherwise considered to belong exclusively to humans. So, on second thought, the possibility of a change of perspective seemed necessary in order to be a little more in alignment with “the ambiguous and provisional nature of sensory experience,” as the philosopher David Abram put it. Abram’s idea that “no phenomenon is utterly passive, without efficacy or influence” increasingly monopolized my thoughts, inviting me to recognize in the slightest manifestation of reality an active influence, with its own agency and a unique role to play in the narrative of my existence. And so, without truly noticing it, as I produced images, as I threw flashes of light into the surrounding darkness or made furtive interventions in the landscape, I became an animist.

5-

Au dos de l’appareil grand format Graflex Crown Graphic se trouve une petite cage métallique rétractable, permettant de faire le foyer rapidement ou de cadrer intuitivement le paysage devant soi, sans l’usage du drap noir et de la loupe. Si je n’ai jamais vraiment profité des avantages offerts par ce dispositif, son inutilité fut toujours compensée par le fait qu’une fois replié, celui-ci assure la protection du verre dépoli qui, lui, est la source d’un émerveillement inégalé. Sous le drap noir, l’image apparaît, reproduction lumineuse de l’espace ayant soudainement perdu sa profondeur au profit d’une illusion faite d’éclats de lumière, de couleurs et de formes. On imagine aisément comment il était possible de s’extasier devant une camera obscura avant l’invention du procédé chimique qui permit de fixer cette image sur un support physique.

Bien que je n’utilisais presque plus cet appareil, il m’arrivait fréquemment de le sortir de son sac de rangement dans l’espoir que cette action m’encouragerait à en faire usage, le numérique s’étant déjà infiltré au sein de ma pratique avec l’assurance du conquérant. Lorsque le mécanisme permettant de retenir les petites plaquettes de métal au-dessus du verre dépoli se brisa, je me résignai enfin à me départir de ce paravent autrement gênant et source d’agacement constant pendant la manipulation de l’appareil. J’avais démonté cette caméra à maintes reprises par le passé, retirant l’objectif et explorant le mécanisme de l’obturateur, soufflant sur la poussière incrustée dans les recoins de la boîte et vérifiant le soufflet extensible. Pourtant, rarement m’étais-je intéressé au dos de l’appareil, plus précisément, au cadre noir du verre dépoli, retenu au boîtier par deux ressorts assez solides pour tolérer les mouvements répétitifs de l’insertion des porte-plaques. Le décrochant de l’appareil, je le déplaçai devant moi, cadrant au hasard des sujets qui disparaissaient dans le flou créé par la couleur blanchâtre du verre semi-opaque. Lorsque je l’approchais d’un objet, celui-ci devenait tout à coup visible en silhouette et cela me fit penser à la technique du photogramme, un type d’images rudimentaires qui conservent à la surface d’un papier la trace de leur contact avec un sujet. Ayant enseigné la fabrication de photogrammes pendant plusieurs années sans jamais ressentir grand enthousiasme à l’égard des résultats, je redécouvrais soudainement une technique de fabrication d’images qui me semblait en phase avec mon désir de parler du contact entre le paysage et moi, entre les éléments et la lumière, entre l’expérience du terrain et la production d’un corpus d’images pouvant témoigner du foisonnement magnifique des êtres et des choses.

Je déposai donc le verre dépoli dans mon sac de randonnée, rangeai le Graflex dans le placard et me promis de sortir bientôt en amenant avec moi cette pièce d’équipement inusitée.

On the back of the Graflex Crown Graphic large-format camera is a small, retractable metal cage, which allows quick focusing or intuitive framing of the landscape ahead without the need for a black cloth and a magnifying glass. Although I never really took advantage of this device, its uselessness was always offset by the fact that, once folded, it protects the ground glass that is the source of incomparable wonder. Beneath the black cloth, the image appears, a luminous reproduction of space that has suddenly lost its depth in favour of an illusion made up of bursts of light, colours, and shapes. It’s easy to imagine how people would have been fascinated by a camera obscura before the invention of the chemical process that made it possible to fix this image on a physical support.

Although I seldom worked with the camera, I often took it out of its travel case, in the hope that this would encourage me to use it again, even though digital technology had infiltrated my practice with a conqueror’s confidence. When the mechanism holding the small metal plates broke, I resigned myself to getting rid of the annoying sunshield, which was a constant bother when I took pictures. I had dismantled this camera many times in the past, removing the lens and exploring the shutter mechanism, blowing away dust embedded in the nooks and crannies of the box, and checking the extendable bellows. Yet, I had rarely investigated the back of the camera – more specifically, in the black frame holding the ground glass, held to the body by two strong springs capable of tolerating the repetitive movement caused by the insertion of film holders. Unhooking it from the camera, I moved it around in front of me, randomly framing subjects that disappeared in the blur created by the whitish colour of the glass. As I approached an object, it suddenly became visible as a silhouette, reminding me of photograms, a rudimentary type of image that preserves on the surface of photosensitive paper the trace of its contact with a subject. Having taught the making of photograms for several years, without ever feeling much enthusiasm “about the results, I was suddenly rediscovering an image-making technique that seemed attuned to my desire to speak of the contact between the landscape and myself, between the elements and the light, between the field experience and the production of a body of work that can bear witness to the magnificent abundance of beings and things.

So, with these thoughts in mind, I put the ground glass in my hiking bag, stored the Graflex in the closet, and promised myself I’d go out soon, bringing this unusual piece of equipment with me.

6-

Alors que j’étais assis au milieu des bois, quelque temps plus tard, un érable à sucre mature se brisa bruyamment sur ma droite et me ramena instantanément dans l’immédiat, stupéfait par la puissance de ce cataclysme forestier. Impressionné et surpris, je me levai de la chaise que j’avais traînée avec moi, confondu par le peu d’émoi qui s’exprima au cœur de la forêt à la suite de ce fracas. Probablement qu’entre les branches ou sous les souches, on se déplaçait en silence, attentif aux suites improbables de l’événement, mais de ces réactions discrètes, je ne reçus aucun écho. À la cime des arbres, le vent faisait valser les feuilles qui se détachaient du ciel dans un contraste étonnant.

Par un curieux hasard, ce bouleversement forestier me sortait de la lecture du livre d’Akiko Busch, intitulé How to Disappear. L’auteur y déployait une réflexion passionnante à propos de la notion d’invisibilité. « Devenir invisible n'équivaut pas à être inexistant. Il ne s'agit pas de nier l'individualisme créatif ni de renoncer à l'une ou l'autre des qualités qui peuvent nous rendre uniques, originaux, singuliers. […] Le camouflage dans le monde naturel n'est pas un trait exotique et pittoresque. Cette faculté est nuancée, créative, sensible, perspicace. Et surtout, elle se révèle puissante ». Puissante, oui, puisqu’elle permet d’éviter d’être vu de ses proies ou de ses prédateurs. L’invisibilité témoigne d’une sensibilité marquée envers son environnement, d’une capacité à s’y fondre prudemment, à y survivre en harmonie avec la multitude, à y agir avec sagacité et discernement.

Mon agitation ayant toutefois troublé le calme nécessaire à cette lecture, je décidai de marcher jusqu’au ruisseau afin de m’y baigner. Une fosse d’une dizaine de mètres de longueur permettait d’y patauger, en se glissant au-dessus des roches qui n’étaient submergées que d’un mètre d’eau au plus profond de la superficie. Souvent, j’y nageais avec mes enfants, les appelant à « faire la truite » avec moi dans ce bassin toujours frais, même au cœur de l’été. Nous étions très loin des capacités de dissimulation du monde animal, alors qu’on voyait clairement les petits poissons déguerpir avec effroi à l’approche de nos corps immenses.

« Mon invisibilité est une affaire de silence et d’immobilité », nous dit Busch. La mienne le sembla aussi lorsque seul au milieu du bassin, je dérivai lentement. Timidement d’abord, les petits poisons s’approchèrent et touchèrent la peau de mes jambes et de mes bras. Ce chatouillement me surprit, mais je laissai ces petites créatures s’approcher pour qu’elles me voient passer d’un corps menaçant à un corps, nourricier, se laissant dévorer avec plaisir.

Sometime later, I was sitting in the middle of the woods when a mature maple tree loudly snapped to my right; I was instantly brought back to the present, stunned by the power of this forest cataclysm. Impressed and surprised, I rose from the chair I’d brought with me, bewildered by how little commotion there was deep in the woods in the wake of this tremendous crash. Some creatures were probably moving silently among the branches or under the stumps, watching for the unlikely aftermath of the event, but I heard none of these discreet reactions. At the treetops, the wind was blowing the leaves, which stood out against the sky in astonishing contrast.

By a curious coincidence, this sudden disruption in the forest occurred while I was reading Akiko Busch’s book How to Disappear. Busch offers a fascinating exploration of the notion of invisibility. She says, “Becoming invisible is not the equivalent of being nonexistent. It is not about denying creative individualism nor about relinquishing any of the qualities that may make us unique, original, singular ... Camouflage in the natural world is not some exotic and picturesque trait. It is nuanced, creative, sensitive, discerning. Above all, it is powerful.” Powerful indeed, as it enables one to avoid being seen by one’s prey or predators. Through various trickery techniques, which Busch articulately describes, the faculty of disguise makes it possible to imitate – to pass oneself off as – an adversary in order to steal a territory or any other object of desire. Invisibility reveals a keen sensitivity to one's environment, an ability to blend in carefully, to survive harmoniously and wisely among the multitude.

But because the excitement had unsettled the calm I needed for my reading, I decided to walk down to the stream for a refreshing dip. There’s a ten-metre-long pool that one can wade in, sliding over rocks submerged by only a metre of water at the deepest point. I often went there with my children, inviting them to “swim like a trout” with me in water that was always cool, even in the heart of summer. We were nowhere near having the concealing capabilities of the animal world, as we could clearly see the little fish scurrying away in fright as our gigantic bodies approached.

“My invisibility is a matter of silence and immobility,” Busch says. So was mine, as I slowly drifted, alone, in the middle of the pool. Shily at first, the little fish approached and touched my legs and arms. The tickling surprised me, but I let the creatures come closer, watching myself change from a threatening body to a nurturing one that let itself be devoured with pleasure.

7-

Sur la rive droite du ruisseau, le terrain s’élevait de manière abrupte. La combinaison d’un sol glaiseux et d’une courbe dans la trajectoire du cours d’eau à cet endroit provoquait un affaissement progressif de cette portion du terrain, qui grimpait dans un escarpement d’une vingtaine de mètres à partir de la berge. Chaque printemps, je venais observer les transformations du paysage, constatant l’effondrement de quelques arbres ayant grandi dans ce sol ingrat et voyant s’agrandir ou se rétrécir mon espace de baignade. Je grimpais parfois dans cet espace où régnait une sorte d’anarchie végétale, mais je ne m’avançais jamais très loin, mes bottes s’enfonçant tôt ou tard dans la terre boueuse.

Lorsque je me trouvais dans l’eau du ruisseau ou sur l’autre rive plus accueillante, je scrutais, intrigué, ce dénivelé chaotique, sachant l’endroit inhospitalier pour un être au pas lourd comme le mien. J’imaginais qu’une foule de petites bêtes, plus légères, y trouvaient une certaine protection. J’imaginais aussi qu’elles m’observaient en silence, intriguées par cette créature qui tentait tant bien que mal de devenir invisible au cœur de la forêt.

Ainsi, en cette fin d’après-midi d’août, poussé par le faible courant du ruisseau, je regardais les mouvements de la lumière, projetés sur les pierres enfoncées dans le lit de la rivière, elles-mêmes bien retenues par la poussée incessante de l’écoulement des eaux et de l’accumulation du sable solidifiant leur position. De l’enchevêtrement de branches qui surplombait ma position me parvint soudainement un autre bruit, celui des pas d’un cerf avançant maladroitement dans ces espaces naturels et farouches. Pendant un moment, mon invisibilité faite de silence et d’immobilité me permit de regarder la bête se frayer un chemin au travers de la végétation. Le soleil baissait et l’animal prenait la mesure du chemin à parcourir avant de rejoindre le sentier battu par ses confrères et consœurs. Du haut de l’escarpement, la scène devait être toute autre et je tentai de me projeter là-haut, regardant en bas ce corps bercé par l’eau fraîche et le soleil. La lumière faiblissait et je me vis, stabilisant mon trépied, réglant l’exposition et la mise au point, prêt à saisir une image de mon corps disparaissant dans l’eau impétueuse de ces espaces partagés.

On the right bank of the stream, the terrain rose steeply. The combination of clayey soil and a bend in the stream’s path was causing a gradual subsidence of this portion of the land, which climbed to an escarpment twenty metres or so from the bank. Every spring, I’d come and observe the changes in the landscape, noting the collapse of a few trees that had grown in this unforgiving soil and seeing my swimming hole expand or shrink. Occasionally, I’d climb into this space where a sort of vegetal anarchy reigned, but I never got very far, as my boots would sooner or later sink into the muddy earth. So, when I found myself in the water of the stream or on the other, more welcoming shore, I scrutinized the chaotic slope, knowing the place to be inhospitable to a being with as a heavy footstep as mine. I imagined that a host of smaller, lighter creatures found shelter and protection in this unruly area. I also imagined that they were silently watching me, intrigued by this animal trying so hard to become invisible in the heart of the forest.

And so, on this August late afternoon, nudged along by the stream’s gentle current, I watched the light’s movements projected onto the stones embedded in the riverbed, firmly held in place by the incessant push of the flowing water and the accumulation of sand solidifying their position. From the overhanging tangle of branches, I suddenly heard another sound: the footfalls of a deer clumsily advancing through these wild natural spaces. For a moment, my invisibility formed of silence and immobility allowed me to watch it make its way through the vegetation. The sun was dropping, and the deer was taking the measure of the distance it had to cover to reach the trail beaten by its companions. From the top of the escarpment, I told myself, the scene must be so different. I visualized myself up there, looking down at my body cradled by fresh water and sunshine. The light was fading, and I saw myself steadying my tripod, adjusting the exposure and focus, ready to capture an image of my own body, disappearing into the rushing water of these shared spaces.

Notes

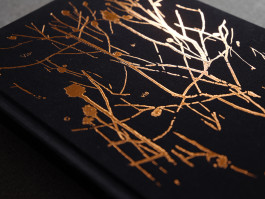

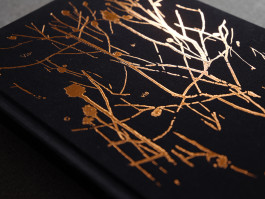

À l’exception de la diapositive numérisée qui ouvre la séquence de ce livre (datant pour sa part de 2006), les photographies présentées ici ont été produites à Montréal et à Sainte-Hélène-de-Chester, au Québec, entre 2019 et 2023.

La citation d’ouverture est issue de Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology, de l’auteur David Abram, publié en 2011 chez Vintage Books. J’y fais également référence plus loin dans le livre. J’en ai fait moi-même la traduction vers le français.

Le livre How to disappear: Notes on Invisibility in Times of Transparency, de l’auteur Akiko Busch, est également cité dans la dernière partie du texte de cet ouvrage. Il a été publié en 2019 chez Penguin Books et la traduction, ici encore, est de moi.

With the exception of the digitized slide that opens the sequence of this book (dating from 2006), the photographs presented here were produced in Montreal and Sainte-Hélène-de-Chester, Quebec, between 2019 and 2023.

The opening quotation is from Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology, by author David Abram, published in 2011 by Vintage Books, New York. I also refer to it later in the book.

How to Disappear: Notes on Invisibility in Times of Transparency, by Akiko Busch, is also quoted in the last part of the text. It was published in 2019 by Penguin Books.

Vis-à-vis est avant tout un projet de livre photographique, édité sous la bannière des Éditions du Renard. Si vous aimez ces images et ce récit, vous pouvez vous procurer une copie du livre en suivant ce lien.

Vis-à-vis is first and foremost a photobook project, published by Éditions du Renard. If you like these words and images, consider purchasing a copy of the book by following this link.

La création de ces photographies a été rendue possible grâce à l’appui financier du Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec.

The creation of these photographs was made possible thanks to the financial support of the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec.

↑

TOP

« En réalité, nous connaissons les choses de notre monde non pas comme des objets fixes et déterminés, mais plutôt comme des personnes familières ou des étrangers, des proches de confiance ou des voisins gênants, des alliés, des marginaux ou des camarades fantasques et, même, dangereux. [...] Tous ces êtres participent, avec moi, à l’émergence continue du réel. Aucun d’entre eux, selon mon expérience, n’est totalement inerte ou inanimé. »

“We know the things of our world not, in truth, as determinate objects, but as acquaintances and strangers, as trusted familiars and as troublesome neighbors, as allies and misfits and moody, dangerous comrades ... All of these beings are participant, with me, in the ongoing emergence of the real. Not one of them, in my direct experience, is utterly inert or inanimate.”

David Abram - Becoming Animal - An Earthly Cosmology

1- Une des dernières images de mon livre Les affluents montre quelques roches formant un bassin circulaire inondé par la marée montante du fleuve Saint-Laurent. Au moment de photographier cette petite installation, je me remémorai les nombreuses fois où j’avais moi-même, d’abord en tant qu’enfant puis en tant que père, assemblé ainsi des pierres afin de créer un enclos marin pour y déposer les petits poissons et les écrevisses capturés lors d’après-midis d’été, passés près du ruisseau coulant sur la terre familiale. Continuer de lire...

Sous un ciel gorgé d’une pluie à venir, je fis quelques images de cet assemblage précaire, sachant que les mouvements de l’eau allaient probablement bientôt le faire disparaître. Plus tard, alors que je travaillais sur mon livre, la symbolique de cette submersion m’apparut signifiante et j’utilisai l’une de ces images pour clore ma série, dont l’objectif était d’évoquer la relation naissante de mes enfants avec la nature et certains lieux importants de notre histoire familiale. La photographie témoignait, me semblait-il, du caractère éphémère de toutes ces expériences qui ont tôt fait de se transformer en vagues impressions lointaines ou en flashs qu’on savoure avec étonnement lors de moments inattendus offerts par la mémoire.

Au-delà des histoires personnelles évoquées par ces pierres submergées, c’était maintenant l’origine de cette intervention furtive qui m’interpellait. Le geste posé sur le paysage symbolisait le dialogue et l’échange, tout comme il représentait les vestiges d’une relation fondée sur l’expérience vécue de ces espaces. Certes, on avait probablement déplacé ces roches naïvement, pour jouer ou simplement pour passer le temps, mais on avait néanmoins parlé au paysage et écrit à sa surface, dans un moment de symbiose auquel je pouvais m’identifier.

One of the last images in my book Les affluents shows some stones forming a circular basin that is being flooded by the rising tide of the St. Lawrence River. As I photographed this human-made arrangement, I recalled the many times that I myself, first as a child and then as a father, had assembled stones in the same way to create a pond in which I would place the small fish caught during summer afternoons spent near the stream running through my family’s land.

Under a sky swollen with rain to come, I made a few images of this precarious structure, knowing that the waves would probably soon wash it away. Later, while working on my book, I found the symbolism of this submersion meaningful, and I used one of these images to conclude the series, in which I wanted to evoke my children’s nascent relationship with nature and certain important places in our family history. The photograph bore witness, I thought, to the ephemerality of all these experiences, which were quickly transformed into vague, distant impressions or flashes to savour with amazement at unexpected moments offered by memory.

Beyond the personal experiences evoked by the submerged stones, the origin of this furtive intervention in the landscape led me to reflect on the nature of the interaction that had occurred at this site. The gesture, it seemed to me, symbolized both dialogue and exchange, just as it represented the vestige of a relationship based on the lived experience of these spaces. Of course, someone had probably moved the rocks innocently, playing or simply passing the time, but they had nevertheless spoken to the landscape and written on its surface in a moment of symbiosis to which I could relate.

2- Mettre fin à un projet laisse habituellement quelques images en suspens, celles étant trop étrangères aux réflexions du moment et ainsi renvoyées à un espace indéfini de la pensée, peuplé de fragments épars et hétéroclites qui formeront éventuellement quelques constellations d’idées nouvelles. C’est en explorant des boîtes remplies de ces images orphelines (parce que ce bel « espace indéfini de la pensée » s’incarne aussi dans quelques boîtes empilées dans les placards et dans d’autres espaces obscurs de la maison) que je retrouvai par hasard une diapositive grand format datant de 2006. On y voit une sorte d’abri fait de branches et d’herbes d’automne, résultat d’un avant-midi de travail en forêt pendant lequel je m’étais adonné au jeu improvisé de la construction d’un petit refuge. La photographie documentant ce travail n’avait jamais trouvé sa place dans mes projets, mais elle résonnait maintenant en harmonie avec quelques intuitions parcellaires. Continuer de lire...

À peu près au même moment de l’année, tandis que je marchais au crépuscule dans un petit boisé près de la maison, la lumière en contre-jour changea drastiquement ma perception des lieux, m’éblouissant dans une sorte d’agressivité inattendue. Ne tolérant pas pour sa part un tel aveuglement, l’appareil photo se dressa devant la lumière sans pouvoir en contenir l’assaut : au centre du cadre de mon image apparut un spectre rosâtre, témoignant des limites technologiques de l’appareil et du caractère parfois étonnamment poétique des effets résultant de celles-ci.

Tout comme pour la photographie du cercle de roches de mon projet précédent, la diapositive retrouvée montrait un geste posé dans le paysage. L’image captée à contre-jour, quant à elle, faisait apparaître l’intervention du paysage à l’intérieur même de mon action photographique. L’une montrait un paysage transformé par mon passage, l’autre la trace que ce même paysage avait laissé sur mon image. J’épinglai ces deux images sur mon mur et retournai à mes lectures.

Bringing a project to an end usually leaves a few images in abeyance, as they’re too foreign to the current reflections and are thus bound for an indefinite space of thought, populated by scattered and heterogeneous fragments that will eventually form a few constellations of new ideas. It was while exploring boxes filled with these orphaned images (because this beautiful “indefinite space of thought” is also embodied in a few boxes piled up in closets and other obscure spaces around the house) that I stumbled across a large-format slide dating from 2006. It shows a shelter of sorts made of branches and autumn grasses, the result of a morning’s work in the forest, where I’d been playing the impromptu game of building a little refuge. The photograph documenting this task had never found its way into my projects, but now it resonated in harmony with a few haphazard intuitions.

Around the same time of year, as I was walking through a small wooded area near my home at dusk, the backlight drastically changed my perception of the surroundings, dazzling me with a kind of unexpected aggressiveness. The camera couldn’t tolerate such blindness or withstand the assault of the light: it created a rose-coloured halo in the centre of my image, testifying to the limitations of its technology and the sometimes surprisingly poetic qualities of the resulting effects.

As had the photograph of the rock circle, the recovered slide showed a gesture made within the landscape. The image captured with the backlight showed the landscape’s intervention in my photographic action. So, one showed a landscape transformed by my passage, the other the trace that this same landscape had left on my image. I pinned these two photographs on my wall and returned to my readings.

3- Je ne savais plus exactement pourquoi j’avais quitté le sentier. La montée était abrupte. Mon oncle, qui habite les lieux, avait pourtant creusé dans la pente naturelle de la terre un chemin de traverse qui lui permettait, au printemps, de remonter avec le tracteur les barils d’eau d’érable ou, le reste de l’année, les longs billots de bois destinés au moulin. S’il avait pris la peine de tracer un chemin afin de nous éviter la difficile remontée vers le rang 3, pourquoi couper ainsi au travers de la pente, au milieu des branches indomptées et d’une terre meuble à peine tenue par les racines des érables et des merisiers ? Continuez de lire...

Malgré l’affection pour ces lieux qui nous unissait, nos rapports à la forêt étaient bien différents. J’admirais secrètement chez mon oncle la connaissance détaillée des changements de la nature, mais très rarement avions-nous partagé notre émerveillement face à une ondée spectaculaire ou une débâcle printanière. Tous deux discrets de nature, nos échanges se limitaient à des observations factuelles quant aux événements ayant marqués les lieux depuis ma dernière visite. L’éboulement avait-il englouti une plus grande part de pente du terrain cette année ? La saison des sucres avait-elle été fructueuse ce printemps ? Intérieurement, je me demandais quelle place pouvait occuper la rêverie dans le quotidien de celui qui doit prendre soin ou tirer profit d’une parcelle de territoire.

En tant que visiteur occasionnel, j’abordais ces espaces avec l’imagination et le pragmatisme du randonneur, détaché de la nécessité de les rendre profitables, que ce soit à des fins de culture acéricole (comme c’était le cas ici) ou pour tout autre usage productiviste. Ainsi, j’étais souvent à la recherche de nouveaux chemins afin d’errer autrement dans ces lieux familiers, n’y cherchant rien de particulier sinon une forme de dépaysement susceptible de m’amener vers de nouvelles images. J’avais hérité du côté cérébral de mon père et bien que l’intelligence d’une belle coupe sélective m’impressionnât – en favorisant, par une certaine aération de la forêt, la pousse des arbres les plus prometteurs –, le flâneur introverti n’était jamais très loin, en attente des dérèglements de l’ordinaire et s’excitant lorsque le réel, soudainement, se glissait dans les habits excentriques de l’insolite.

Toujours est-il que je m’agrippais aux petites pousses des peupliers, jaugeant leur capacité à résister à l’étirement que je leur infligerais, et tentant du même coup d’éviter le piège d’un petit tronc en apparence sain à sa base, mais qui me ferait perdre l’équilibre parce que complètement sec à sa cime, mort parmi le vivant.

I no longer knew exactly why I had left the trail. It was a steep ascent. My uncle, who lived on the property, had dug a path across the natural slope of the land so that in spring he could haul up the barrels of maple sap with the tractor, and the rest of the year the long logs bound for the mill. If he’d taken the trouble to lay out a path so that we wouldn't have to make the difficult climb up to the road, why cut across the slope here, amid untamed branches and loose soil barely held together by the roots of the maple and cherry trees?

Despite our shared affection for these places, our relationship with the forest was very different. I secretly admired his detailed knowledge of nature’s transformations, but very rarely had we shared our wonder when faced with a spectacular storm. We were both discreet by nature, and our exchanges were limited to factual observations on the events that had marked the area since my last visit. Had the landslide swallowed up more of the slope this year? Had the maple sugaring season been fruitful this spring? Inwardly, I wondered what part daydreaming could play in the daily life of someone who has to care for or profit from a piece of land.

As an occasional visitor, I approached these spaces with the imagination and pragmatism of a hiker, detached from the need to make them profitable, whether for maple syrup production (as was the case here) or for any other productive use. As a result, I was often on the lookout for new ways to wander these familiar places, seeking nothing in particular other than a change of scenery that might lead me to new images. I had inherited my father’s cerebral side, and although I was impressed by the intelligence of a fine selective cut – which favours the growth of the most promising trees by thinning the forest – I was never very far from the introverted flâneur, waiting for disturbances of the ordinary and getting excited when the real suddenly slipped into the eccentric garments of the unusual.

Still, I grabbed onto little poplar saplings, testing their capacity to bear my pulling on them. At the same time, I was trying to avoid the trap of supporting myself on a small trunk that looked healthy but would cause me to lose my balance because its crown was completely dry – the dead among the living.

4- Malgré l’automne tardif, les rayons du soleil me réchauffaient le dos tout en éclairant le terrain devant moi d’une lumière presque perpendiculaire à la pente. Quelques champignons ayant survécu à l’assaut des premières gelées, les écorces depuis longtemps tombées, les aiguilles d’une épinette noire et l’émanation fraîche de l’humidité du sol s’harmonisaient à l’effort physique me laissant haletant et m’obligeant à m’arrêter pour souffler un peu. Une fois retourné vers la lumière, j’aperçus par une trouée dans les arbres la pente douce qui remontait de l’autre côté de la rivière, formant ainsi une vallée respectable en dépit du peu d’altitude que ces dénivelés arrivaient à atteindre. Continuer à lire...

Sur le sol, une longue racine attira mon attention. Enroulée presque parfaitement sur elle-même, elle formait un cercle mystérieux qui évoquait un symbole issu d’un autre lieu et d’un autre temps. Que la nature me parlât, je n’en avais aucun doute : mon corps entier ressentait chaque instant passé en forêt, humait les odeurs, ressentait les textures des éléments que je touchais dans mes déplacements et écoutait la faste trame sonore des bois. Mais qu’un langage fait de symboles et de signes pouvant être lus ou interprétés puisse exister – cela faisait appel à un degré de fantaisie que je n’étais pas complètement prêt à me reconnaître.

Il y avait cependant ce balai de sorcière qui, à contre-jour, m’était apparu plus tôt comme le curieux présage d’un nœud intérieur à défaire afin de faire confiance à ma pratique de l’image, paraissant parfois étrangères aux approches contemporaines du médium. Il y avait aussi cette souche d’arbre, polie par le passage de l’eau à sa surface, coincée dans le lit de la rivière et se transformant en ossements lisses, comme un squelette résilient. J’avais trouvé là une pierre, elle aussi bien bloquée dans un espace qui ne semblait pas lui être destiné, mais créant tout de même un alliage d’une beauté surprenante. J’y voyais la manifestation d’une faculté de créativité, cette impulsion autrement considérée comme appartenant exclusivement à l’humain. À bien y réfléchir, la possibilité d’un changement de perspective semblait maintenant nécessaire afin d’être un peu plus « en phase avec la nature ambiguë et provisoire de l'expérience sensorielle », comme le disait le philosophe David Abram. Celui pour qui « aucun phénomène n'est totalement passif, sans efficacité ni influence » accaparait de plus en plus mes pensées, m’invitant à reconnaître dans la moindre manifestation du réel une influence active, ayant sa propre agentivité et son rôle unique à jouer dans la trame narrative de mon existence. Ainsi, sans trop m’en rendre compte, à mesure que je produisais des images, que je lançais les coups de flash lumineux dans la noirceur environnante ou que je réalisais quelques interventions furtives dans le paysage, je devenais animiste.

Despite the late autumn, the sun’s rays warmed my back and illuminated the terrain ahead with a light that was almost perpendicular to the slope. A few mushrooms that had survived the assault of an early frost, long-fallen tree bark, the needles of a black spruce, and the fresh scent of moist soil harmonized with the physical effort that left me panting and forced to stop for a breather. As I turned back toward the light, I could see through a gap in the trees the gentle slope that rose on the other side of the river, forming a respectable valley despite the low altitude that these hills were able to reach.

On the ground, a long root caught my eye: it curled almost perfectly around itself, forming a mysterious circle and evoking a symbol from another time and place. That nature spoke to me I had no doubt, as my whole body felt every moment spent in the forest – smelling the odours, feeling the textures of the things I touched as I went, and listening to the rich soundtrack of the woods. But that there could be such a thing as a language, made up of symbols and signs that could be read or interpreted, appealed to a degree of fantasy that I wasn’t quite ready to admit to myself.

There was, however, a witch’s broom that, with backlighting, had struck me earlier as a curious omen of an inner knot to be untied in order to trust my image-making practice, which sometimes seems at odds with contemporary approaches to the medium. There was also a tree stump, polished by the passage of water over its surface, wedged in the riverbed and being transformed into what looked like smooth bones, a resilient skeleton. A stone, also lodged where it seemingly shouldn’t be, created a surprisingly beautiful assemblage. I saw it as a manifestation of creativity, that impulse otherwise considered to belong exclusively to humans. So, on second thought, the possibility of a change of perspective seemed necessary in order to be a little more in alignment with “the ambiguous and provisional nature of sensory experience,” as the philosopher David Abram put it. Abram’s idea that “no phenomenon is utterly passive, without efficacy or influence” increasingly monopolized my thoughts, inviting me to recognize in the slightest manifestation of reality an active influence, with its own agency and a unique role to play in the narrative of my existence. And so, without truly noticing it, as I produced images, as I threw flashes of light into the surrounding darkness or made furtive interventions in the landscape, I became an animist.

5- Au dos de l’appareil grand format Graflex Crown Graphic se trouve une petite cage métallique rétractable, permettant de faire le foyer rapidement ou de cadrer intuitivement le paysage devant soi, sans l’usage du drap noir et de la loupe. Si je n’ai jamais vraiment profité des avantages offerts par ce dispositif, son inutilité fut toujours compensée par le fait qu’une fois replié, celui-ci assure la protection du verre dépoli qui, lui, est la source d’un émerveillement inégalé. Sous le drap noir, l’image apparaît, reproduction lumineuse de l’espace ayant soudainement perdu sa profondeur au profit d’une illusion faite d’éclats de lumière, de couleurs et de formes. On imagine aisément comment il était possible de s’extasier devant une camera obscura avant l’invention du procédé chimique qui permit de fixer cette image sur un support physique. Continuer de lire...

Bien que je n’utilisais presque plus cet appareil, il m’arrivait fréquemment de le sortir de son sac de rangement dans l’espoir que cette action m’encouragerait à en faire usage, le numérique s’étant déjà infiltré au sein de ma pratique avec l’assurance du conquérant. Lorsque le mécanisme permettant de retenir les petites plaquettes de métal au-dessus du verre dépoli se brisa, je me résignai enfin à me départir de ce paravent autrement gênant et source d’agacement constant pendant la manipulation de l’appareil. J’avais démonté cette caméra à maintes reprises par le passé, retirant l’objectif et explorant le mécanisme de l’obturateur, soufflant sur la poussière incrustée dans les recoins de la boîte et vérifiant le soufflet extensible. Pourtant, rarement m’étais-je intéressé au dos de l’appareil, plus précisément, au cadre noir du verre dépoli, retenu au boîtier par deux ressorts assez solides pour tolérer les mouvements répétitifs de l’insertion des porte-plaques. Le décrochant de l’appareil, je le déplaçai devant moi, cadrant au hasard des sujets qui disparaissaient dans le flou créé par la couleur blanchâtre du verre semi-opaque. Lorsque je l’approchais d’un objet, celui-ci devenait tout à coup visible en silhouette et cela me fit penser à la technique du photogramme, un type d’images rudimentaires qui conservent à la surface d’un papier la trace de leur contact avec un sujet. Ayant enseigné la fabrication de photogrammes pendant plusieurs années sans jamais ressentir grand enthousiasme à l’égard des résultats, je redécouvrais soudainement une technique de fabrication d’images qui me semblait en phase avec mon désir de parler du contact entre le paysage et moi, entre les éléments et la lumière, entre l’expérience du terrain et la production d’un corpus d’images pouvant témoigner du foisonnement magnifique des êtres et des choses.

Je déposai donc le verre dépoli dans mon sac de randonnée, rangeai le Graflex dans le placard et me promis de sortir bientôt en amenant avec moi cette pièce d’équipement inusitée.

On the back of the Graflex Crown Graphic large-format camera is a small, retractable metal cage, which allows quick focusing or intuitive framing of the landscape ahead without the need for a black cloth and a magnifying glass. Although I never really took advantage of this device, its uselessness was always offset by the fact that, once folded, it protects the ground glass that is the source of incomparable wonder. Beneath the black cloth, the image appears, a luminous reproduction of space that has suddenly lost its depth in favour of an illusion made up of bursts of light, colours, and shapes. It’s easy to imagine how people would have been fascinated by a camera obscura before the invention of the chemical process that made it possible to fix this image on a physical support.

Although I seldom worked with the camera, I often took it out of its travel case, in the hope that this would encourage me to use it again, even though digital technology had infiltrated my practice with a conqueror’s confidence. When the mechanism holding the small metal plates broke, I resigned myself to getting rid of the annoying sunshield, which was a constant bother when I took pictures. I had dismantled this camera many times in the past, removing the lens and exploring the shutter mechanism, blowing away dust embedded in the nooks and crannies of the box, and checking the extendable bellows. Yet, I had rarely investigated the back of the camera – more specifically, in the black frame holding the ground glass, held to the body by two strong springs capable of tolerating the repetitive movement caused by the insertion of film holders. Unhooking it from the camera, I moved it around in front of me, randomly framing subjects that disappeared in the blur created by the whitish colour of the glass. As I approached an object, it suddenly became visible as a silhouette, reminding me of photograms, a rudimentary type of image that preserves on the surface of photosensitive paper the trace of its contact with a subject. Having taught the making of photograms for several years, without ever feeling much enthusiasm “about the results, I was suddenly rediscovering an image-making technique that seemed attuned to my desire to speak of the contact between the landscape and myself, between the elements and the light, between the field experience and the production of a body of work that can bear witness to the magnificent abundance of beings and things.

So, with these thoughts in mind, I put the ground glass in my hiking bag, stored the Graflex in the closet, and promised myself I’d go out soon, bringing this unusual piece of equipment with me.

6- Alors que j’étais assis au milieu des bois, quelque temps plus tard, un érable à sucre mature se brisa bruyamment sur ma droite et me ramena instantanément dans l’immédiat, stupéfait par la puissance de ce cataclysme forestier. Impressionné et surpris, je me levai de la chaise que j’avais traînée avec moi, confondu par le peu d’émoi qui s’exprima au cœur de la forêt à la suite de ce fracas. Probablement qu’entre les branches ou sous les souches, on se déplaçait en silence, attentif aux suites improbables de l’événement, mais de ces réactions discrètes, je ne reçus aucun écho. À la cime des arbres, le vent faisait valser les feuilles qui se détachaient du ciel dans un contraste étonnant. Continuer de lire...

Par un curieux hasard, ce bouleversement forestier me sortait de la lecture du livre d’Akiko Busch, intitulé How to Disappear. L’auteur y déployait une réflexion passionnante à propos de la notion d’invisibilité. « Devenir invisible n'équivaut pas à être inexistant. Il ne s'agit pas de nier l'individualisme créatif ni de renoncer à l'une ou l'autre des qualités qui peuvent nous rendre uniques, originaux, singuliers. […] Le camouflage dans le monde naturel n'est pas un trait exotique et pittoresque. Cette faculté est nuancée, créative, sensible, perspicace. Et surtout, elle se révèle puissante ». Puissante, oui, puisqu’elle permet d’éviter d’être vu de ses proies ou de ses prédateurs. L’invisibilité témoigne d’une sensibilité marquée envers son environnement, d’une capacité à s’y fondre prudemment, à y survivre en harmonie avec la multitude, à y agir avec sagacité et discernement.

Mon agitation ayant toutefois troublé le calme nécessaire à cette lecture, je décidai de marcher jusqu’au ruisseau afin de m’y baigner. Une fosse d’une dizaine de mètres de longueur permettait d’y patauger, en se glissant au-dessus des roches qui n’étaient submergées que d’un mètre d’eau au plus profond de la superficie. Souvent, j’y nageais avec mes enfants, les appelant à « faire la truite » avec moi dans ce bassin toujours frais, même au cœur de l’été. Nous étions très loin des capacités de dissimulation du monde animal, alors qu’on voyait clairement les petits poissons déguerpir avec effroi à l’approche de nos corps immenses.

« Mon invisibilité est une affaire de silence et d’immobilité », nous dit Busch. La mienne le sembla aussi lorsque seul au milieu du bassin, je dérivai lentement. Timidement d’abord, les petits poisons s’approchèrent et touchèrent la peau de mes jambes et de mes bras. Ce chatouillement me surprit, mais je laissai ces petites créatures s’approcher pour qu’elles me voient passer d’un corps menaçant à un corps, nourricier, se laissant dévorer avec plaisir.

Sometime later, I was sitting in the middle of the woods when a mature maple tree loudly snapped to my right; I was instantly brought back to the present, stunned by the power of this forest cataclysm. Impressed and surprised, I rose from the chair I’d brought with me, bewildered by how little commotion there was deep in the woods in the wake of this tremendous crash. Some creatures were probably moving silently among the branches or under the stumps, watching for the unlikely aftermath of the event, but I heard none of these discreet reactions. At the treetops, the wind was blowing the leaves, which stood out against the sky in astonishing contrast.

By a curious coincidence, this sudden disruption in the forest occurred while I was reading Akiko Busch’s book How to Disappear. Busch offers a fascinating exploration of the notion of invisibility. She says, “Becoming invisible is not the equivalent of being nonexistent. It is not about denying creative individualism nor about relinquishing any of the qualities that may make us unique, original, singular ... Camouflage in the natural world is not some exotic and picturesque trait. It is nuanced, creative, sensitive, discerning. Above all, it is powerful.” Powerful indeed, as it enables one to avoid being seen by one’s prey or predators. Through various trickery techniques, which Busch articulately describes, the faculty of disguise makes it possible to imitate – to pass oneself off as – an adversary in order to steal a territory or any other object of desire. Invisibility reveals a keen sensitivity to one's environment, an ability to blend in carefully, to survive harmoniously and wisely among the multitude.

But because the excitement had unsettled the calm I needed for my reading, I decided to walk down to the stream for a refreshing dip. There’s a ten-metre-long pool that one can wade in, sliding over rocks submerged by only a metre of water at the deepest point. I often went there with my children, inviting them to “swim like a trout” with me in water that was always cool, even in the heart of summer. We were nowhere near having the concealing capabilities of the animal world, as we could clearly see the little fish scurrying away in fright as our gigantic bodies approached.

“My invisibility is a matter of silence and immobility,” Busch says. So was mine, as I slowly drifted, alone, in the middle of the pool. Shily at first, the little fish approached and touched my legs and arms. The tickling surprised me, but I let the creatures come closer, watching myself change from a threatening body to a nurturing one that let itself be devoured with pleasure.

7- Sur la rive droite du ruisseau, le terrain s’élevait de manière abrupte. La combinaison d’un sol glaiseux et d’une courbe dans la trajectoire du cours d’eau à cet endroit provoquait un affaissement progressif de cette portion du terrain, qui grimpait dans un escarpement d’une vingtaine de mètres à partir de la berge. Chaque printemps, je venais observer les transformations du paysage, constatant l’effondrement de quelques arbres ayant grandi dans ce sol ingrat et voyant s’agrandir ou se rétrécir mon espace de baignade. Je grimpais parfois dans cet espace où régnait une sorte d’anarchie végétale, mais je ne m’avançais jamais très loin, mes bottes s’enfonçant tôt ou tard dans la terre boueuse. Continuez de lire...

Lorsque je me trouvais dans l’eau du ruisseau ou sur l’autre rive plus accueillante, je scrutais, intrigué, ce dénivelé chaotique, sachant l’endroit inhospitalier pour un être au pas lourd comme le mien. J’imaginais qu’une foule de petites bêtes, plus légères, y trouvaient une certaine protection. J’imaginais aussi qu’elles m’observaient en silence, intriguées par cette créature qui tentait tant bien que mal de devenir invisible au cœur de la forêt.

Ainsi, en cette fin d’après-midi d’août, poussé par le faible courant du ruisseau, je regardais les mouvements de la lumière, projetés sur les pierres enfoncées dans le lit de la rivière, elles-mêmes bien retenues par la poussée incessante de l’écoulement des eaux et de l’accumulation du sable solidifiant leur position. De l’enchevêtrement de branches qui surplombait ma position me parvint soudainement un autre bruit, celui des pas d’un cerf avançant maladroitement dans ces espaces naturels et farouches. Pendant un moment, mon invisibilité faite de silence et d’immobilité me permit de regarder la bête se frayer un chemin au travers de la végétation. Le soleil baissait et l’animal prenait la mesure du chemin à parcourir avant de rejoindre le sentier battu par ses confrères et consœurs. Du haut de l’escarpement, la scène devait être toute autre et je tentai de me projeter là-haut, regardant en bas ce corps bercé par l’eau fraîche et le soleil. La lumière faiblissait et je me vis, stabilisant mon trépied, réglant l’exposition et la mise au point, prêt à saisir une image de mon corps disparaissant dans l’eau impétueuse de ces espaces partagés.

On the right bank of the stream, the terrain rose steeply. The combination of clayey soil and a bend in the stream’s path was causing a gradual subsidence of this portion of the land, which climbed to an escarpment twenty metres or so from the bank. Every spring, I’d come and observe the changes in the landscape, noting the collapse of a few trees that had grown in this unforgiving soil and seeing my swimming hole expand or shrink. Occasionally, I’d climb into this space where a sort of vegetal anarchy reigned, but I never got very far, as my boots would sooner or later sink into the muddy earth. So, when I found myself in the water of the stream or on the other, more welcoming shore, I scrutinized the chaotic slope, knowing the place to be inhospitable to a being with as a heavy footstep as mine. I imagined that a host of smaller, lighter creatures found shelter and protection in this unruly area. I also imagined that they were silently watching me, intrigued by this animal trying so hard to become invisible in the heart of the forest.

And so, on this August late afternoon, nudged along by the stream’s gentle current, I watched the light’s movements projected onto the stones embedded in the riverbed, firmly held in place by the incessant push of the flowing water and the accumulation of sand solidifying their position. From the overhanging tangle of branches, I suddenly heard another sound: the footfalls of a deer clumsily advancing through these wild natural spaces. For a moment, my invisibility formed of silence and immobility allowed me to watch it make its way through the vegetation. The sun was dropping, and the deer was taking the measure of the distance it had to cover to reach the trail beaten by its companions. From the top of the escarpment, I told myself, the scene must be so different. I visualized myself up there, looking down at my body cradled by fresh water and sunshine. The light was fading, and I saw myself steadying my tripod, adjusting the exposure and focus, ready to capture an image of my own body, disappearing into the rushing water of these shared spaces.

Notes

À l’exception de la diapositive numérisée qui ouvre la séquence de ce livre (datant pour sa part de 2006), les photographies présentées ici ont été produites à Montréal et à Sainte-Hélène-de-Chester, au Québec, entre 2019 et 2023.

La citation d’ouverture est issue de Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology, de l’auteur David Abram, publié en 2011 chez Vintage Books. J’y fais également référence plus loin dans le livre. J’en ai fait moi-même la traduction vers le français.

Le livre How to disappear: Notes on Invisibility in Times of Transparency, de l’auteur Akiko Busch, est également cité dans la dernière partie du texte de cet ouvrage. Il a été publié en 2019 chez Penguin Books et la traduction, ici encore, est de moi.

With the exception of the digitized slide that opens the sequence of this book (dating from 2006), the photographs presented here were produced in Montreal and Sainte-Hélène-de-Chester, Quebec, between 2019 and 2023.

The opening quotation is from Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology, by author David Abram, published in 2011 by Vintage Books, New York. I also refer to it later in the book.

How to Disappear: Notes on Invisibility in Times of Transparency, by Akiko Busch, is also quoted in the last part of the text. It was published in 2019 by Penguin Books.

Vis-à-vis est avant tout un projet de livre photographique, édité sous la bannière des Éditions du Renard. Si vous aimez ces images et ce récit, vous pouvez vous procurer une copie du livre en suivant ce lien.

Vis-à-vis is first and foremost a photobook project, published by Éditions du Renard. If you like these words and images, consider purchasing a copy of the book by following this link.

La création de ces photographies a été rendue possible grâce à l’appui financier du Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec.

The creation of these photographs was made possible thanks to the financial support of the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec.

↑

TOP